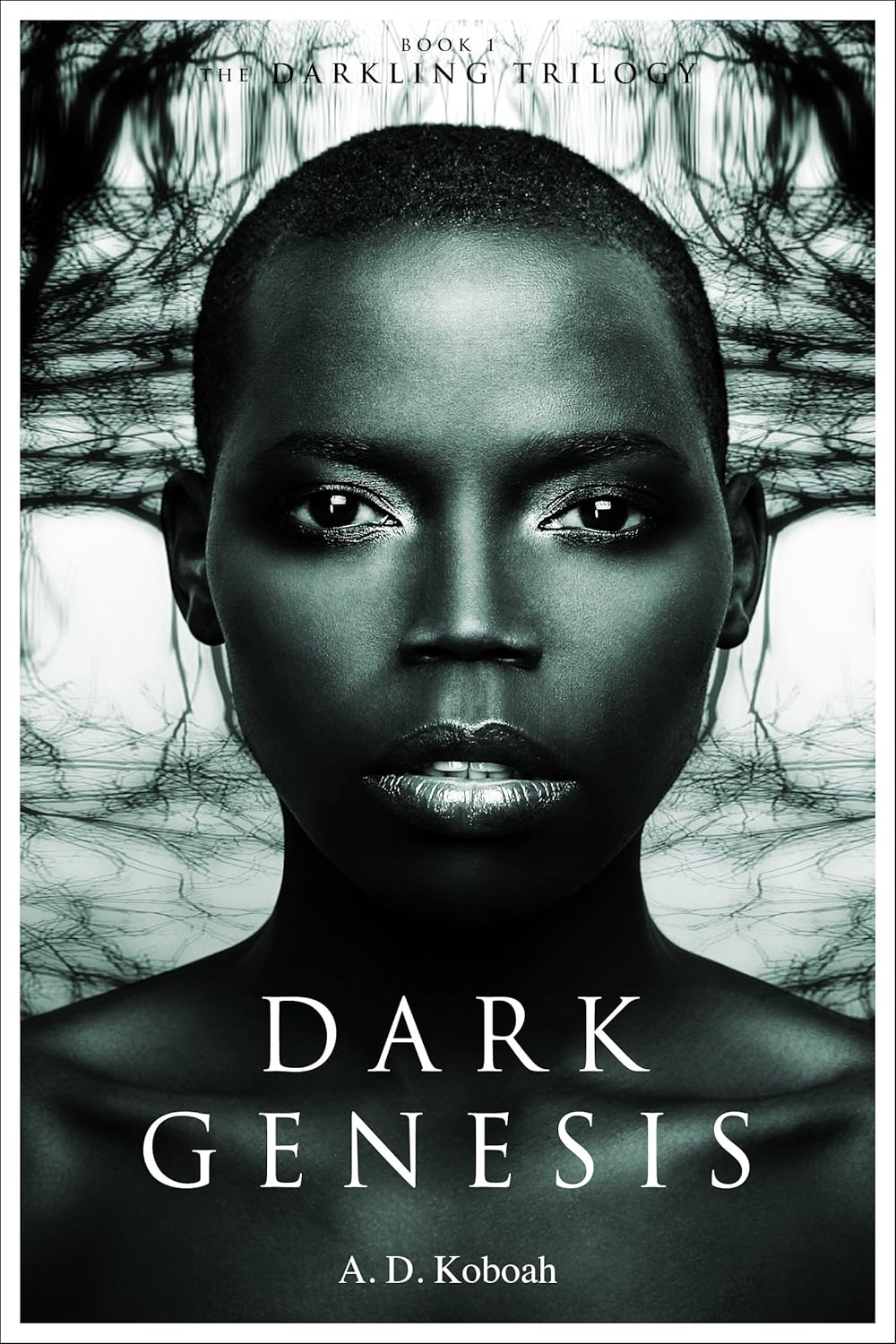

Life for a female slave is one of hardship and unspeakable sorrow, something Luna knows only too well. But not even she could have foreseen the terror that would befall her one sultry Mississippi evening in the summer of 1807.

Life for a female slave is one of hardship and unspeakable sorrow, something Luna knows only too well. But not even she could have foreseen the terror that would befall her one sultry Mississippi evening in the summer of 1807.

On her way back from a visit to see the African woman, a witch who has the herbs Luna needs to rid her of her abusive master’s child, she attracts the attention of a deadly being that lusts for blood. Forcibly removed from everything she knows by this tormented otherworldly creature, she is sure she will be dead by sunrise.

Dark Genesis is a love story set against the savage world of slavery in which a young woman who has been dehumanised by its horrors finds the courage to love, and in doing so, reclaims her humanity.

Targeted Age Group:: Adult

What Inspired You to Write Your Book?

My debut novel Dark Genesis was inspired by my thoughts on dehumanisation. I was fascinated by the ways in which people are able to dehumanise others, the impact it has on the psyche and whether it is possible for people to find their way back from being dehumanised. This led me to Luna and the ruins of a haunted chapel deep in the heart of Mississippi.

How Did You Come up With Your Characters?

In most of the novels and films about vampires that are out at the moment, being a vampire is seen as something desirable. But I have always thought that being made into a vampire is something that would isolate you from the rest of society – effectively dehumanising you. That is what I had in mind when I started thinking about my vampire novel and I envisioned this vampire who has been alone for decades and has all but forgotten who he is. I asked myself what kind of a heroine would be able to understand this vampire, let alone fall in love with him? Only a young woman who has also been dehumanised by society: A slave called Luna.

Book Sample

Chapter One

My name is Luna and my tale begins on a dry summer evening in 1807.

I was walking quickly along a dusty country road, my shoes stirring up a small cloud of dust that turned the hem of my faded violet dress a muddy brown. The trail of dust I left in my wake soon settled. But the pressing need that had me make this two-hour journey in beaten shoes and a broken spirit, in the midst of a particularly merciless Mississippi summer, would not be settled as easily. Wiping the sweat from my brow and waving away the flying insects that droned lazily near my face, I wished for some respite from the relentless heat but found none. Although the sun hung low in the topaz blue sky, it felt as if I were walking through warm soup and it was likely to stay like this long after the sun went down.

I would have found some relief from the pitiless sun if I had chosen to walk through the woods that rose up on either side of the road like a green and brown wall. But green woody spaces such as those have been a deep source of fear for me since I was a child and I imagined that they would continue to be so long past what I guessed was my twenty-second or twenty-third year on this Earth. So I clutched my lantern and small cloth bundle and walked on in the heat, listening to the birdcalls punctuate the otherwise still air.

I was lucky to be able to make this journey during the summer months as the previous two trips had been made in the dead of winter when night gathered up the day long before I could finish serving the family’s supper and slip away, leaving the other house slaves to do my share of work and conceal my absence. That small mercy meant that I didn’t have to walk alone in the dark, afraid to light my lamp in case the solitary glow brought unwanted attention my way, or have to dive into the trees every time the sound of a horse’s hooves disturbed the sweet melody of the crickets. It also meant that when I turned the corner and saw the woodland give way to cotton fields, marking the beginning of the Marshall plantation, there was still roughly two hours of daylight left, which meant I would be able to finish my business and be back before dark, hopefully before I was missed by my hawk-eyed mistress.

I stopped for a second to gaze at the rows of cotton up ahead. I have always thought that there was something heavenly about cotton fields, which looked like row upon row of fleecy white clouds caught up in brown nets. But I’m sure that the brown-skinned figures bent double between those rows would have disagreed. For them, there was nothing even remotely celestial about the cotton fields in which they had been toiling since sunrise. And they were likely to still be working in them when the sun set. Even from this distance I could see that most of them were wretchedly thin, their few flimsy items of clothing in tatters. And although I wasn’t close enough to see their faces, I was sure that they all wore uniform expressions of misery and fatigue.

I left that unhappy sight and ducked into the trees on my left, a necessary shortcut to the slave quarters. Although many slaves have used this shortcut on their way to see the African woman, I’m sure I’m the only one who ran all the way through the trees looking back over my shoulder even though I knew I wasn’t being followed. Only when I saw a flash of white through the trees did I slow down so my breathing could return to normal by the time I exited the screen of trees.

The slave quarters were little white cabins made of wood, which lay in two long rows some distance from the Master’s mansion. Only a few children were around at this hour, some of whom recognised me and stopped what they were doing to stare with a quiet reverence that made me uncomfortable. It was the same reverence I had received from the grownups the last two times I had come here under the cover of darkness and they had not only stopped what they were doing to watch me pass by, but nodded or offered some sort of greeting, which I returned before hurrying on by. I didn’t have to endure that kind of scrutiny today, but I still hurried down to the lone cabin at the back of the clearing, which was nestled under the shadow of the trees some distance away from the rest of the slave quarters.

Many slaves came to visit Mama Akosua for her medicines, and her skills were known far and wide. It was also rumoured that she dealt in more than just herbs and was actually a witch. Whether that was true or not, she was feared by many, even some of the whites, and few dared incur her wrath.

As I got nearer to the cabin, I saw that the door had been left open and a light was burning inside even though the sun had yet to go down. I approached gingerly. Already feeling the unease that always possessed me in the presence of the African woman, I walked up to the door, and stopped.

“Mama Akosua.”

There was a short spell of silence and then her voice floated out to me.

“I have been expecting you.” The voice was low and dry like the sound of rustling leaves.

She probably said that every time someone came to her door, no doubt to help foster the belief that she was a powerful all-seeing, all-knowing witch. But the words still sent icy fingers trailing down my spine and I swallowed before taking her words as permission to enter.

The cabin, which consisted of only one room, was rich with the slightly bitter, but not unpleasant, smell of dried herbs. Most of the room was taken up by a long wooden table, which held bottles, bowls and an assortment of other instruments that were used to prepare her concoctions. Every wall in the room was lined with shelves holding bottles, jars and baskets of fresh and dried herbs. The only evidence that someone lived in the cabin was the pallet in the corner. This was the most furniture I had seen in any slave cabin, but as her Master profited from the sale of her herbs, it was in his interest to make sure she had everything she needed. There was another smaller table in the centre of the room and that is where she sat, peering at me by the light of an oil lamp.

She was a small lithe woman with delicate features like mine. Her head was cleanly shaven and she would have been considered beautiful were it not for the scars, rows of lines about an inch long, marking her forehead and cheeks. It was rumoured that those scars had been self-inflicted when she was first brought to America as a slave. Some people whispered that she had done it to honour the customs of her people, others, that the journey, the horrors of the middle passage, had driven her to scar her face in madness and despair. Although I would never dare to ask her, I didn’t believe she had been driven insane. The shrewd dark eyes that met mine belonged to a strong, sharp mind and I doubted that anything could, or ever would, be able to break it.

“Evening, Mama Akosua,” I said as I walked into the circle of light.

There was still daylight outside but it didn’t seem to reach the small window in Mama Akosua’s cabin and so it was always dark in here no matter what the time of day.

She gestured to the chair opposite hers, her eyes never leaving my face. I moved to the chair and when I sat down, she pushed a small cup toward me.

“Drink,” she said.

I picked up the cup and sipped the cool concoction, which tasted vaguely of mint leaves. Whatever it was, it seemed to have an immediate effect because I no longer felt as hot and the fatigue, which had been pulling on me like lead weights, seemed to evaporate.

Feeling slightly better, I was able to meet the force of her gaze fully. She seemed to have aged a great deal since I last saw her, nearly four years ago. The lines around her eyes and the ones running from her nose to the corners of her mouth had deepened and although she was not yet forty years old, she looked much older.

She studied me for a few moments and a soft sigh escaped her when she finally shifted her gaze away from my face.

“It is as I feared,” she said and stood up, wincing from the small movement.

“You hurt?”

“It is a small price to pay,” she mumbled, more to herself it seemed.

She reached into a basket on one of the shelves and pulled out a small black cloth bundle. Moving back to the table she placed the bundle before her and when she sat down again she closed her eyes for a few seconds. She was clearly in a lot of pain.

“I have prepared what you need,” she said, pulling open the cloth bundle to reveal six paper sachets of herbs.

There was no need for her to ask me why I was here. I would only risk making this dangerous journey for one reason.

“Take this tonight.” She pointed to the larger of the bundles. “The rest is to be taken for five nights after, to stop the bleeding.”

She tied up the bundle and pushed it across the table toward me.

“Thank you, Mama Akosua.”

“Is it the son this time?”

I looked up and met her intimidating gaze, but on this occasion, I couldn’t hold it. She knew how much these things shamed me yet it didn’t stop her from asking about them. When I answered, my voice was barely a whisper.

“Yes.”

“How long?”

“He…he be at my cabin near about three times a week now since Easter.”

“He is worse than his father, no?” It wasn’t a question; it was a statement.

“Yes.”

I fought back tears as an image came to me from a few weeks before. I was standing in my tiny cabin and Master John was behind me gazing at our reflections in a small handheld mirror. I don’t know if making me look at myself was one of the many ways he had of tormenting me or if he really was oblivious to the fact that I despised my face. Either way, he would make me stare at my piercing dark brown eyes framed by long sooty eyelashes, deep mahogany skin, small delicate features and large sensuous lips. My springy, unruly hair was pulled away from my face, something he insisted on, as my hair was the one thing a man like him could find no beauty in. It was always the same ordeal with the mirror whenever he came to my cabin. And I honestly don’t know which face I hated more, that of the blond-haired, blue-eyed man I had come to despise even more than his old, decrepit father, or my own. The face he was enamoured with. He eventually pulled the mirror out of my hand, and placing it on the windowsill, held his arms out.

“Dance with me,” he had said in a soft, silky voice.

I remained where I was, my face a blank mask but rage no doubt burning behind my eyes. I may not have had a say over his nocturnal visits, but I would not play these little games or pretend that I wanted him in my wretched little cabin.

Fast, so fast that I didn’t have time to protect myself, he raised his hand and slapped me, sending me crashing to the floor. Pain bloomed along my temple and the left side of my face. I had also bitten my lip when I hit my head. His foot came down on my neck and I felt the dirt on the sole of his boot rubbing into my skin as he pressed down, cutting off my air supply. I struggled in vain to breathe and was close to losing consciousness when he slowly removed his foot and hauled me back onto my feet as if he were picking up a sack of potatoes. Then he held out his arms again, that smile, which never seemed to leave his face, swimming before my eyes as I struggled to clear my vision.

I was bristling with anger and yet fear won out because he could do anything he wanted to me and there was nothing I would be able to do to stop him. No one I could go to for protection. I had been born and bred purely for men like him, not only to do with as they pleased, but to increase their riches by breeding more slaves for them to own.

“Dance with me,” he said again.

Tasting blood in my mouth, I did as I was ordered to do.

“Massa Henry used to please hisself and leave,” I told Mama Akosua. “But Massa John…he like to play.”

I sensed rather than saw her rage.

I had led a relatively painless existence, for a slave, up until around the age of eight or nine when Master Henry had sent me on an errand to one of the neighbouring farms, an errand which would take me through the woods. I had run eagerly out of the house, hardly believing the good fortune that meant I could spend most of the morning walking through the woods instead of working. And it was the perfect day for a long walk, a beautiful spring day. The air was crisp and cool and the sun filtering through the fresh green leaves created patches of golden haze for me to walk through. I skipped along carefree and untouched at that time by the burdens of a female slave, deviating from my path only once to chase a squirrel, losing it moments later when it darted up a tree and out of sight.

It wasn’t long before I came to a stream winding its way through the trees directly in my path and saw Master Henry on his horse. I froze straight away but wasn’t immediately frightened as it seemed his face lit up with the kind of excitement you would expect to see on the face of a man on a long quest for buried treasure at the moment he finally finds it.

“Massa Henry!” I cried, dropping the parcel he had given me to deliver. I stooped to pick it up and when I straightened, he had already dismounted and was walking quickly toward me.

Master Henry, who was in his fifties, was tall and thin, had brown hair that was peppered with grey, a beak of a nose and thin, pink lips. I felt immediately uneasy about being on my own with him so far from the house, especially since it seemed as if he had gone to the trouble of saddling up his horse and riding out of the plantation with the sole intention of overtaking me.

But I tried to allay my fears by telling myself that he had never actually given me reason to fear him. The only unnerving thing about him was that he had a habit of turning up wherever I was working and would watch me intently for far too long as if he were looking to find fault with my work. He had never actually reprimanded me for anything, but something about his manner, his long wrinkled neck, bony elbows and knees, reminded me of a vulture waiting patiently. Mary, the cook, seemed uneasy about his apparent interest in my work. Perhaps she was worried that if he found fault with anything I did it would be blamed on her. So whenever Master Henry was at home she was always beside me, helping me with my chores even though I was more than capable of doing them on my own, a light sheen of anger marking her every action, the quick furtive glances she cast in Master Henry’s direction always fearful. Sometimes she would find an excuse to call me away if Master Henry made his way into whatever room I was in. I noticed that the other house slaves did the same.

I was too young at that time to know why his greedy eyes had become my shadow or why he showed such an overt interest in everything I did. I was also too young to understand the acid rage I saw in his young wife Mistress Emily’s eyes whenever she saw him watching me, or why she had tried on more than one occasion to send me to work in the fields. And the other slaves obviously thought it was kinder not to explain it to me.

So when I saw him waiting for me that day, I knew I was in a lot of trouble but I didn’t know what I had done.

When he got to me I saw a feverish light in his eyes as they moved over my tiny body. It was as if he couldn’t see or hear anything but me. Then his hand shot out abruptly and he pushed me to the ground. When he began to wrestle with his belt I tried to crawl away, knowing now that something awful was about to happen. But he was already on top of me, ripping my dress off whilst he moaned and reached for my chest to paw at what had not yet begun to form there. The pain had been horrific and my screams seemed to heighten his pleasure as he rode me as if I were the stallion he had obviously ridden furiously in order to catch me here alone in the woods. I lost consciousness at some point, and when I came to it was to the sight of him pulling up his trousers. He had mounted his horse and then turned to look at me with what I now know to be lust and it was clear that he was considering getting off his horse to repeat what he had done. Thankfully he gently urged his horse on through the trees to make his way back to the road.

Once he was gone I rolled onto my side and sobbed. I didn’t fully understand what had happened, but I knew it was something to be ashamed of and that I couldn’t go back to the house and face Mary. There was a faintly metallic smell mingling with that of the cold dry earth and I realised that it was the smell of my own blood, which was seeping through my legs. I tried to cover myself but my dress was torn in two so I wrapped my arms around what was left of the garment and lay there crying.

After a while, when the sun had reached the highest point in the sky, the sound of a twig snapping under the weight of a person’s foot told me I was no longer alone.

I sat up with a start to see one of the slaves, Jupiter, standing about three metres away from me. He was a tall, handsome African of around eighteen years old and had coal black skin and big beautiful brown eyes. I used to find excuses to go to the fields along with some of the other slave girls so that we could catch a glimpse of him toiling under the relentless heat of the Mississippi sun and we would run away giggling whenever he saw us watching him. Those days seemed like a lifetime away from where we were now, watching each other under the emerald leaves. And I noticed that the haunting quality that had been in his eyes since he had arrived at the plantation a few months ago had been replaced with a mixture of rage and despair.

He abruptly lowered his eyes and removed his shirt as he strode toward me. Fear shot through me. I screamed in terror and made a feeble attempt to try and scurry away, thinking that he meant to do what Master Henry had done. My reaction made him jump and he looked at me in bewilderment before taking in his own naked chest. Making the connection between his actions and my apparent fear, he shook his head in alarm and then threw the shirt on the ground before taking a few steps back.

Breathing harshly, I watched him point to his shirt, then to me, and he mimicked wrapping something around himself.

He hadn’t spoken a word since arriving at the plantation and all efforts to teach him English had failed. Master Henry had come to the conclusion that he was dumb, but some of the other slaves thought it was only an act.

I tried to rise, and when the pain between my legs reared up, I froze and remained on my knees crying until Jupiter slowly moved toward me. I eyed him warily through my tears as he picked up his shirt. When it became apparent to him that I was in too much pain to try and move away, he gently laid the shirt over my shoulders and pulled me to my feet, grimacing at my cry of pain. I let him button the large shirt around me, and when it was done, he took a few steps forward and gestured for me to follow.

I ground my teeth together and tried to walk without letting a scream escape my lips and he let me take a few steps like that before he abruptly closed the space between us and swiftly picked me up.

“Naw!” I screamed. “Naw!”

I tried to slap at his chest and face as he began to run through the trees with me in his arms.

“Please. Please. We hurry,” he panted in a gruff, heavily accented voice as he tried to dodge my tiny hands. “Your pain. Please.”

I stopped my feeble attempts, surprised to hear that the other slaves had been right. He could speak. He carried me back to the plantation, his coal black skin glistening with my blood by the time we got there to the quiet anger and dismay of the other slaves.

What I will never forget about that day was Mistress Emily walking into Mary’s quarters where I lay sobbing whilst a distraught Mary tried to clean me and tend to the damage that had been done. A small, pale redhead, she stood over me, her eyes gleaming with unshed tears and her anger so pure and intense that I was sure she would find a way to make Master Henry pay for what he had done. But I saw my error with the next words she spoke.

“I want you back in the kitchen now!” she said to Mary.

“But…but Mistress—” Mary had stuttered but she was soon silenced.

“I said I want you back in the kitchen, and if dinner is even one minute late, I’ll whip you myself.”

Mary had gotten to her feet slowly, her hands balled into fists at her side and her hazel brown eyes a cauldron of barely concealed hatred. For a moment, unease passed over Mistress Emily’s face and it seemed like an unbearably long moment before Mary spoke again.

“Y…yes, Miss Emily,” she mumbled.

Shaking with anger, she quickly wiped away her tears and glancing helplessly at me, bowed her head and left the cabin.

Left alone with Mistress Emily, I lay as still as I could, trying to ignore the pain down below as I choked back my tears. The look she gave me in those few seconds before she left the cabin was one of such hatred that I was chilled to the bone. I will never forget it.

Jupiter never spoke to me or even looked me in the eye again after that day. Whenever I saw him he would drop his gaze and nod politely but he never stayed in my presence for long. Of all the things I had to endure during the years that followed, having Jupiter never look me in the eye was no doubt the worst. I never forgot his kindness that day, but I knew that seeing me soiled had changed his view of me in a fundamental way, and even though it was painful for me to accept, I understood it and so kept my distance from him. He was sold a few years later and although I missed his presence on the plantation, it was a relief not to have him avert his gaze or find a reason to get away from me whenever our paths crossed.

The wounds I sustained that day healed, but the mental scars never left me alone.

Neither did Master Henry.

He found every opportunity to accost me again and again. Three years passed and his weekly visits only stopped when my breasts and stomach began to grow. I hadn’t known why I was sometimes sick in the morning and why my appetite had increased, until Mary, who was the closest thing that I had to a mother, explained that I would soon have a child of my own.

The child came on a devilishly cold winter night under the fury of a raging storm, the worst that anyone could remember ever being unleashed on Mississippi. I screamed out in pain as a contraction rippled through my stomach with almost as much force as the wind and rain lashing against my tiny cabin. It was a Sunday so my mind was still crowded with the sermon I had heard at church during the day, the story of Noah and the Great Flood taking on greater meaning in my panic-stricken mind. It felt like the end of days for me, and as hour after hour passed, the pain and the storm began to take on biblical proportions until I was sure that morning would never come.

Mary was equally anxious. She had come to my cabin thinking that this was another false labour, the third one that week. But it soon became clear, not only that this was the real thing, but that there was something seriously wrong. She was about to leave to go and get help when Mama Akosua, knowing somehow that she was needed, entered the cabin. Mama Akosua had been sold when I was about three, so I only recognised her because of the scars on her face. I had been screaming at the time as another contraction ripped through me and yet in the midst of the pain, the panic and sense of doom left me the moment I laid eyes on her. When she came closer, I stifled another cry when I saw the look of black thunder on her face.

“I will kill him,” she had spat and I guessed that she was talking about Master Henry. “I will cut out his heart with my bare hands. I will kill him.”

Her face hadn’t lost that rage even as she set to work, ordering Mary to boil water or get more rags. It was an extremely difficult birth, complicated by the fact that my womb had only dilated a few centimetres. If Mama Akosua hadn’t been there with her herbal medicines to help me fully dilate, both I and the child she delivered a few hours later would be dead.

When I first heard the baby scream, a sound not unlike the squeal of a pig being slaughtered, I immediately turned my head away, repulsed by this thing that would always remind me of that day in the woods and the years of torment that followed.

For a few moments there was only the sound of the rain lashing the cabin and the awful sound of the baby’s screams. Then at last Mary spoke, the relief and excitement in her voice unable to completely mask the clenching sorrow I could hear flitting around her words.

“You a mama now, Luna. You got you a baby girl.” Her voice wavered on the word “girl”.

“Take it away,” I heard myself say.

“Hush now, Luna. You—” Mary began but I didn’t let her finish.

“Take it away! I don’t care what you does with it. Just take it away!”

I secretly hoped that she would kill that thing and for a moment I thought Mama Akosua had heard my thoughts because she was glaring at me. As frightened as I was by her expression, I kept my eyes on her and pleaded silently with her to take the baby away. The cold fury left her after a few moments and I knew then that she would do as I asked.

I never saw the child again and I don’t know what became of it. It was often on the tip of my tongue to ask Mama Akosua and I’m sure she expected to hear the question every time I saw her. But I couldn’t bring myself to ask because I still hated that thing and I didn’t want to know whether it lived or had died.

I was whipped when they discovered the baby was gone, the first time Master Henry ever took a whip to me. I accepted each stroke of the lash with dead eyes and barely a murmur, feeling far removed from the shocking pain and the warm rivers of blood running from the open wounds on my back and down my legs to lie in a glistening red pool on the ground. The weeks that followed were a pain-tinged blur in which I repeatedly begged death to wrap its tender arms around me. During those weeks I walked a tightrope between life and death, but two faces kept drawing me back toward the barb-tipped snare of life: Mary’s during the day, and Mama Akosua’s at night. She was there every night forcing me to drink some foul-tasting mixture or rubbing something into the open wounds on my back. I would often wake from a restless sleep to hear her singing to me softly in her native tongue. I didn’t understand the words but there was so much sorrow in her voice that it was hard for me to turn my back on life and slip into the arms of death. The anger I had seen the night I gave birth was slowly smoothed down by exhaustion but it was still there as, night after night, she made the long walk from the Marshall plantation to nurse me back to health. I also recall the frequent but fleeting spectre of Master Henry’s tall, stooping figure as he stood in the doorway of my cabin blotting out the sunlight. If it had been any other slave, they would have paid with their life. But Master Henry wanted me too much to ever consider killing me and he fretted that he had perhaps been too hasty in taking the whip to me so soon after I had given birth. But I recovered and nothing was the same after that.

I told everyone that I couldn’t remember what had happened during the birth. I told them that I went to sleep alone and the next thing I remembered was waking up in the morning to the sight of blood everywhere and the knowledge that I had somehow delivered the baby during the night but had no idea what had happened to it.

Nobody believed my story, especially since I kept referring to the child as “it” and didn’t bother to hide my hatred and revulsion every time she was mentioned. From that moment on, the other slaves began to keep their distance from me, probably believing that I had killed the child with my bare hands. I can’t say that I cared either way what they believed as I knew that if I hadn’t been given another option, that is exactly what I would have done rather than let Master Henry have her.

Only Mary knew the truth and she couldn’t tell anyone because if Master Henry ever found out that she was involved in any way, he wouldn’t have hesitated to kill her. So she kept quiet, even though I saw how painful it was for her to hear what was said about me and not be able to defend me with the truth. She also refused to let me push her away. No matter what I said or did, she kept finding ways past the wall I erected until I eventually stopped trying to shut her out. And I believe that even if she hadn’t known what had really happened that night, she would never have forsaken me, because Mary was loyal and the closest thing that I had to a mother.

The visits from Master Henry continued for years until he suffered a stroke. Then they became less frequent until another stroke put an end to them altogether. I was left alone for a year until Master John, Master Henry’s son from a previous marriage, came to take over the daily running of the plantation. That’s when the nightmare began all over again.

About the Author:

I am of Ghanaian descent and spent the first few years of my life in Ghana before moving to London which is where I have lived ever since. I completed an English Literature degree in 2000, and although I have always written in my spare time, I didn’t start writing full-time until a few years ago. My debut novel Dark Genesis was inspired by my thoughts on dehumanisation. I was fascinated by the ways in which people are able to dehumanise others, the impact it has on the psyche and whether it is possible for people to find their way back from being dehumanised. This led me to Luna and the ruins of a haunted chapel deep in the heart of Mississippi.

Links to Purchase Print Books

Link to Buy Dark Genesis Print Edition at Amazon

Links to Purchase eBooks

Link To Buy Dark Genesis On Amazon

Link to Dark Genesis on Barnes and Noble

Link to Dark Genesis for sale on Smashwords

Link to Dark Genesis for sale on iBooks